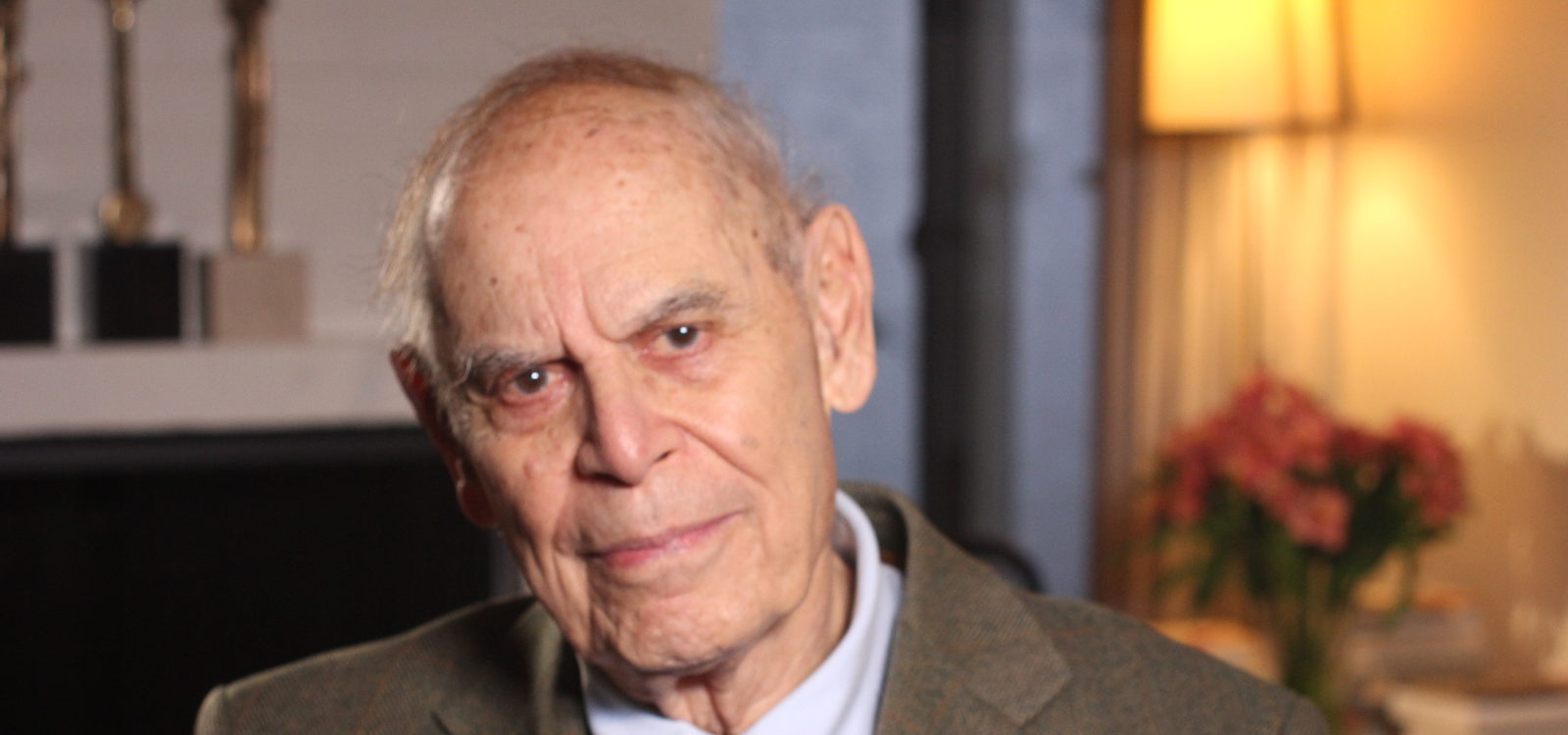

A tribute to Professor Gerald Holton on his 103rd birthday

Professor Gerald Holton, Professor of Physics and History of Science at Harvard University, has just celebrated his 103rd birthday. To mark the occasion, the BBVA Foundation wishes to pay tribute to him by recalling the significance of his work, as recognized by the committee that awarded him the Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Humanities in 2021 “for his numerous seminal contributions to the history of 19th and 20th century science.” We also take this opportunity to republish the video interview and the acceptance speech he delivered following his reception of the BBVA Foundation’s award. His lucid vision of the role of science as a central civilizing force and unifying factor for humanity is hugely relevant in view of the complex problems facing today’s global society. Happy birthday, Professor Holton!

25 May, 2025

Gerald Holton is a towering figure in the study of how science shapes a society’s culture, and the ways in which the cultural matrix of each historical period intimately conditions the practice of science by informing the elaboration of theories and models.

By the time of Holton’s birth, in 1922 Berlin, fascist gangs were already attacking Jewish politicians and intellectuals, a dramatic situation that led his family – the father a lawyer, the mother a physiotherapist – to take refuge in their native Austria. Holton grew up in Vienna, but by 1938 the tentacles were spreading, as evidenced by the terrifying Night of Broken Glass.

By pure chance – the destination of fleeing children was decided by a draw – Holton, his brother and a further 10,000 children were able to leave without their parents for the United Kingdom, with the aid of the Quaker organization Kindertransport. There Holton studied electrical engineering, until in 1940 he was able to rejoin his family in the United States. At the time some American universities were offering places to European refugees, and Holton was able to enroll at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, where he earned a physics degree in 1941, and a master’s in the same discipline in 1942.

During the Second World War he was invited, as were many other physicists, to join the Manhattan Project working on the atomic bomb at Los Alamos (New Mexico). Holton turned down the offer, a decision he ascribes to his respect for the spiritual values of the Quakers who had cared for him in Britain. He did, however, contribute to the war effort in what he considered a defensive role, teaching navy officers how to use radar, and forming part of the military research team stationed at Harvard.

After the war, in 1947, he obtained his PhD from Harvard with a study on the structure of matter at high pressure, under the supervision of Percy Williams Bridgman, a brilliant scientist distinguished with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1946. His association with Harvard, where he developed his entire career as a historian of science, has continued to this day.

The role of science in shaping the culture of each age

Holton’s work upholds the importance of science in shaping the culture of each age, without ever falling into scientificism, the belief that beyond scientific language lie only irrationality and meaninglessness. On the contrary, he argues that many fields, art and literature among them, are instrumental in giving form and content to a society’s culture. He sees science, however, as an essential civilizing force, contributing not only to economic growth and societal welfare but also, at a deeper level, to the configuration of modes of thinking, decision-making and behavior in each time period, on both the individual and collective plane.

The pillars of science – he reminds us – are truthfulness, objectivity and the generation of knowledge that is not immutable but subject to scrutiny by others, and therefore always open to revision in the light of new evidence or more elegant and general conceptual models. So as well as health, economic growth and technological efficiency, science fosters rationality and thus enhances society’s ability to solve its problems.

Yet his work has also shown how science itself does not develop in a capsule, isolated from the cultural (not just socioeconomic) fabric, but rather permeates through it in breadth and depth. Or as Holton explained in the video interview recorded following his reception of the Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Humanities, “science is part of a tapestry, it is woven into a culture.” His distinctive style of investigating the history of science is characterized by his focus on its conceptual and cultural dimensions.

Scientific culture as a unifying force for humanity

Holton was also one of the first voices calling for an urgent and imperative effort to educate the general public in scientific culture, a cause he has advocated for over half a century in a way that is both perceptive and respectful of other sources of general culture. And not just because of the immediate utility of scientific knowledge, but because scientific thought can aid in cognitive orientation, and the construction and development of society’s mental maps or mindset.

From this perspective, Holton is among the authors who has most incisively pinned down the phenomenon of “anti-science,” while alerting to the manifold dangers such attitudes pose. In a number of his articles, he insists that although science may be advancing, there is no guarantee that a society’s general culture will advance in the same direction.

Holton witnessed the rise of Nazi barbarism with his own eyes in an apparently civilized society, and from that early experience has warned with the utmost force and clarity that the cult of irrationality, when combined with populism and nationalism, is an equation whose result all too easily leads to totalitarian movements and regimes: “The record from Ancient Greece to Fascist Germany and Stalin’s USSR to our day shows that movements to delegitimize conventional science are ever present, and ready to put themselves at the service of other forces that wish to bend the course of civilization their way.”

His work ultimately represents a robust defense of scientific rationality as a unifying force for humanity. As he himself put it in his acceptance speech for the Frontiers of Knowledge Award: “My research and publications have sought to understand the cultural contributions of science as a central civilizing force, fostering rationality and objectivity, and the many challenges it has confronted from early modernity to the present day.”